A CRITICAL REVIEW OF INTERVIEW TECHNIQUES OF GENTLEMEN WITHOUT A LAND BETWEEN BORDERS

FADI ABU ZUHRI

INTRODUCTION

A “man without land between borders” can be understood as a stateless person where he either has no nationality or has ineffective nationality because of lack protection from his state of origin, if it exists. The first one refers to de jure statelessness, as Arendt (2004) would define as someone who lost his citizenship due to a recognizable fact and no state will consider him as a national. The second one is de facto statelessness which the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (2005) defined as a person who cannot prove he is de jure stateless but in fact, he has no nationality in effect and does not enjoy the protection benefits of a national.

More so, a stateless person in general does not possess most rights provided to a citizen. Oftentimes, they are exposed to greater risks of persecution which leaves them as one of the most marginalized sectors of the society.

According to figures obtained from various government sources, at least 10 million people around are without a nationality. They are denied basic human rights like education, healthcare, employment (UNCHR, 2017). These people are neither refugees nor displaced by the war in their countries. The condition of these persons has led many states to convene to lobby actions for their protection. As of now, many legal instruments have already been adopted in all parts of the world. The strength of Universal Declaration of Human Right which was established in 1948 has formally provided protection to the stateless persons and further emphasized that every person has a right to have his own nationality. To give strength to UDHR, various legal instruments have been promulgated on the regional and international levels which aimed to protect stateless persons, prevent their increase and establish their nationality.

This article is about the condition of statelessness and how these vulnerable people are interviewed. Facts and best practices have been gathered to synthesize the most proper approach in interviewing these stateless people with an intention of optimizing the time during the interview and gathering the most significant information from them. This study aims to gain in-depth understanding of the treatment of stateless persons especially during the process of documentation and evidence gathering in order to facilitate their plight for residency.

REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE

The review of related literature tackles the condition of statelessness and various published articles and guidelines on how interview is conducted specifically to those who are victims of human rights violations, i.e. stateless persons.

The Handbook on Protection of Stateless Persons (2014) provides that the condition of statelessness is determined through a varied assessment of facts and the law. Most cases of statelessness cannot be adjudged by merely focusing on the agreed nationality laws but also how these laws are executed, if it’s in compliance with the international laws protecting statelessness. As such, there are two categories of evidence that must be obtained, to wit: any proof that relates to the person’s personal circumstances such as his family backgrounds etc. and evidence as to the nationality laws of the putative country. (UNHCR, 2014)

There are number of interview methods provided specifically suited to gather information from stateless persons. This section tackles on few known approach used such as the Cognitive Interview (CI) method, Conversation Management (CM), Achieving Best Evidence (ABE) and the PEACE method . PEACE is an acronym that stands for: Planning and Preparation, Engage and Explain, Account, Closure, and Evaluate.

Interview is defined simply as “a conversation with a purpose” (Hodgson, 1987), but in criminal cases, this definition needs a broader perspective. As such, to get accurate, relevant and complete information from the interviewee, investigative interviewers have to put aside many of the characteristics that are features of everyday conversations, such as interrupting the other person and asking closed questions (Baldwin, 1993; McGurk, Carr, & McGurk, 1993; Milne & Bull, 1999). Different interview techniques has been developed overtime to increase efficiency in gathering relevant information for speedy process of crime fighting and these models are Cognitive Interview (CI), Conversation Management (CM), PEACE Interview and Achieving Best Evidence (ABE).

Cognitive Interview (CI) is a witness-centred approach of interview with a transfer of control to the interviewee who has the sought-after information. The interviewer acknowledges that he/she was not at the scene and that the witness must play an active role in the interview. Toward this end, the CI protocol promotes effective rapport development and teamwork instead of placing the witness in a subservient or reactionary role to an authority figure who asks closed-ended questions. Witness-compatible questioning further ensures that traumatized victims believe they have an ally in what they have gone through. The communication components of the CI are likely to heighten the witness’s sense of control, perhaps restoring some of the power that was lost in the victimization. Finally, the review and closure stages of the CI protocol underscore the important role that the interviewee has played in the process, leaving the witness with a sense of being appreciated. (Fisher & Geiselman, 1992)

In CI, interviewers make a more concerted effort throughout the interview and in follow-up sessions to develop a strong sense of personal concern. Following such a humane policy ought to promote a sense of dignity for the victim and a belief that the interviewer is concerned about the victim’s plight and is not merely fulfilling his/her official responsibility as a criminal investigator. We expect this victim-as-a-person approach to increase victims’ willingness to participate in these modules are very similar to the elements of the CI protocol. Explaining the ground rules up front and fostering a sense of teamwork are considered central. Building rapport, effective listening, and sharing control with the interviewee also are key. Thus, cognitive interviewing and journalistic interviewing are largely consistent with respect to recommended questioning of victims and witnesses of stressful events. (Fisher & Geiselman, 2010)

Conversation Management (CM) started when the psychologist Dr. Eric Shepherd trained police officers of the London City Police in the early 1980s. Shepherd worked out a script for managing any conversation with any person a police officer would be likely to meet. In the context of this training, Shepherd coined the term Conversation Management (CM), which means that the police officer must be aware of and manage the communicative interaction, both verbally and non-verbally (Milne & Bull, 1999).

Conversation Management (CM) has stood the test of time and diversity of application, emerging as a proven ethical, effective approach to ‘finding out’ that yields evidentially sound outcomes. CM is a tool that is applicable to any investigative interviewing context. It combines empirical research findings in cognitive and social psychology and sociolinguistics, with research into reflective practice, skilled practitioner performance, counseling psychology and psychotherapy practice. (Forensic Solutions, 2011)

CM comprises three phases: the pre-, the within- and the post-interview behaviour. In the within-interview phase, the interviewer is encouraged to pay attention to four sub-phases: Greeting, Explanation, Mutual Activity and Closure, abbreviated as GEMAC (Milne & Bull, 1999). The greeting phase concerns an appropriate introduction of the interviewer, which means establishing rapport. In the explanation phase, the interviewer must set out the aims and objectives, and develop the interview further. Mutual activity concerns the elicitation of narration from 4 the interviewee and subsequent questions from the interviewer. Closure is the important phase in which the interviewer should create a positive end of the interview, aiming at mutual satisfaction with the content and performance of the session. The key to continuing into the explanation and the information-gathering phases of CM seems to be establishing rapport. (Holmberg, 2004)

PEACE (Planning and Preparation, Engage and Explain, Account, Closure, and Evaluate (UNCHR, 2017)) is an interview model used in a number of countries around the world that is applicable to interviewing suspects, witnesses and victims (UNODC, 2009). The PEACE model was developed by police and has been used extensively by police both in the United Kingdom and other western countries. While theoretically based the PEACE interviewing model is also informed by the practical and pragmatic perspective of everyday policing. From 1993, the police service in England and Wales undertook a vast programme of PEACE training but by 2000 evaluations showed it had not lived up to expectations. Reasons include minimal support from management, lack of buy-in from supervisors, inconsistent implementation, and limited resources to develop and maintain the programme (Clarke & Milne, 2001).

Achieving Best Evidence (ABE) provides guidance on how to interview vulnerable and intimidated witnesses. It is generally used to interview victims of serious crimes such as sexual offences and serious assault. The ABE approach should be utilized in trafficking interviews and is applicable in every phase of an interview. (UNODC, 2009)

Achieving Best Evidence (ABE) guidance describes good practice in interviewing witnesses, including victims, in order to enable them to give their best evidence in criminal proceedings. It considers preparing and planning for interviews with witnesses, decisions about whether or not to conduct an interview, and decisions about whether the interview should be video recorded or whether a written statement would be more appropriate (Communicourt, 2011). It applies to both prosecution and defence witnesses and is intended for all persons involved in relevant investigations, including the police, adults and children’s social care workers, and members of the legal profession. This model focused on effective communication, where it is centralized on a level and pace that the child or vulnerable adult can understand.

CONCLUSION

Though a stateless person is devoid of his civil and political rights in connection with his putative country, the 1954 Convention on Human Rights entitled him the right for individual interview. The stateless person’s right to interview and the provision of an interpreter, if seen necessary, is vital to make sure that such stateless persons are given ample opportunity to present their cases, establish their claim and provide necessary evidence supporting their claim. This procedural guarantee provided by the 1954 Convention allows the interviewer, be it person authorized statelessness determination authority or any other person similar in function, to dig deeper on the data gathering and interview to clarify ambiguities of the interviewee’s case (UNHCR, 2014).

Nash (2011) of Asylum Aid provided his organization’s approach in interviewing stateless persons. He stated that there should be a good balance between legal and sociological research elements. With these, he came up with a semi–structured interview approach which aimed to cover key themes such as the person’s circumstances of becoming stateless; his immigration history prior entering to the state where he is now; his current living conditions, and; his profile and statelessness. In this approach, it is given that the questions are rather flexible or optional, which highly depends on the willingness of the interview to provide information. Nash (2011) rather avoided exhaustive kind of interviews in this approach. In addition to the interviews, there are also case file reviews that are provided to complement the interviews. The objectives of this case files is to gather substantial information about the history of immigration of the interview and the grounds of his claim of being stateless. (Nash, 2011)

The UNHCR (2014) stated that the conduct of interview with a stateless person is a significant opportunity for the state authorities or Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) staffs to expound his inquisition based on the given evidence. Because of this, UNHCR advised that using the approach of open-ended questioning is highly recommended as it provided a non-adversarial ambience where the interviewee can feel confident and secure. This can result a willing interviewee who can provide a full account of his situation without any reluctance. The interviewee is expected to give his answer based on his best abilities even there may be details that cannot be provided correctly. If needed, it is advisable to conduct follow-up interviews for the benefit of the stateless person. (UNHCR, 2014)

It must be ensured that during the interview the interviewer practice confidentiality. This is one of the main concerns in the process of interview of stateless persons. Because of this, vital information can be withheld just because the interviewee is not confident for the safety of his information that might risk his chances in getting residency or citizenship. UNHCR thus, advise that early on, the interviewer has already established rapport with the interviewee where there is already trust between them. It should be understood that stateless persons are already experiencing abuse or at risk of abuse, so their fear of persecution is already well-founded. The interviewer has an upper hand in manoeuvring the interview process by ensuring confidentiality, protection and security of the interviewed stateless person. This effort also extended to the interpreter present and those involved in the interview, they all must ensure that the statements given must be kept in secret. (UNHCR, 1995)

Basic procedural right of a stateless person is the right to be interviewed. As such, it is important that such interview process be conducted in such a way that it will benefit the interviewee. Based on the foregoing literatures, it can be observed that there is leniency in gathering testimonial statement from the interview, questions are given in an open-ended approach so as to attain a comfortable atmosphere, strict confidentiality is ensured so as to gather unrestricted information from the interviewee, and lastly, entrusted interpreters are provided so as the statements that will be provided will not be limited by language barriers.

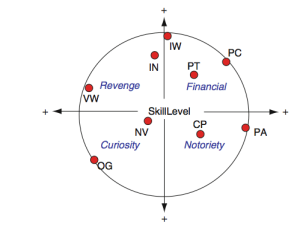

Following the earlier discussions, PEACE and ABE were found to lack a humane approach in dealing with stateless persons. The author recommends an interview technique that is a combination of CI and CM, builds a rapport with the interviewee by valuing their emotional and cultural differences. Such an approach requires the interviewer to acquire Emotional Intelligence (EQ), Cultural Intelligence (CQ) and People Intelligence (PQ).

REFERENCES

1.Arendt, H. (2004). The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York : Schocken Books.

2.Baldwin, J. (1993). Police interview techniques – establishing truth or proof? British Journal of Criminology , 33, 325-351.

3.Clarke, C., & Milne, R. (2001). National evaluation of the PEACE investigative interviewing course. Home Office, UK: Police Research Award Scheme, Report No: PRSA/149.

4.Communicourt. (2011). Achieving Best Evidence. From http://www.vulnerablewitness.co.uk/?page_id=16

5.Fisher, R. P., & Geiselman, R. E. (1992). Memory-enhancing techniques in investigative interviewing: The cognitive interview. Springfield, IL: C.C. Thomas.

6.Fisher, R. P., & Geiselman, R. E. (2010). The Cognitive Interview method of conducting police interviews: Eliciting extensive information and promoting Therapeutic Jurisprudence. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry , 321-328.

7.Forensic Solutions. (2011). Conversation Management. From Forensic Solutions: http://www.forensicsolutions.co.uk/CM.htm

8.Hodgson, P. (1987). A practical guide to successful interviewing. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill .

9.Holmberg, U. (2004). Police interviews with victims and suspects of violent and sexual crimes: Interviewees’ experiences and interview outcomes. University of Stockholm .

10.McGurk, B., Carr, M., & McGurk, D. (1993). Investigative interviewing courses for police officers: an evaluation. In Police Research Series: Paper No.4. London: Home Office.

11.Milne, R., & Bull, R. (1999). Investigative interviewing; Psychology and practice. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

12.Nash, C. (2011). Lessons Learned: UNHCR/Asylum Aid report Mapping Statelessness in United Kingdom. Retrieved April 25, 2017 from European Network on Statelessness: http://www.statelessness.eu/sites/www.statelessness.eu/files/attachments/resources/ENS%20kick-off%20seminar%202012%20-%20Mapping%20Statelessness%20in%20the%20UK.pdf

13.UNCHR. (2017). Ending Statelessness. Retrieved 2017 from http://www.unhcr.org/stateless-people.html

14.UNHCR. (1995). Interviewing Applicants for Refugee Status (RLD 4). Retrieved April 25, 2017 from REFWORLD.ORG: http://www.refworld.org/pdfid/3ccea3304.pdf

15.UNHCR. (2013). Statistics of Stateless Persons. Retrieved April 25, 2017 from UNHCR: http://www.unhcr.org/protection/statelessness/546e01319/statistics-stateless-persons.html

16.UNHCR. (2014). The Handbook on Protection of Stateless Persons. Geneva: UNHCR.

17.UNODC. (2009). Anti-human trafficking for criminal justice practitioners. New York: United Nations.