FINANCIAL INTELLIGENCE WITHIN CYBERCRIME

FADI ABU ZUHRI

INTRODUCTION

Financial Fraud or Financial Crime covers a range of criminal acts or offences that extend beyond national borders. These offences are international in nature and executed in Cyberspace (Boorman & Ingves, 2001). They impact financial sectors and international banking. These form of crimes affect organizations, nations, as well as individuals, negatively impact the social and economic system and cause considerable loss of money. These crimes involve Money Laundering, embezzlement, theft, skimming, Money Laundering, Ponzi schemes and phishing to name a few (Assocham, 2015).

These are often committed by organized criminal networks and motivated by prospects of earning huge profits from the activities. Assets are obtained illegally through Financial Fraud. The differences between countries, including differences in national jurisdictions, the level of expertise of different countries’ prosecutorial and investigative authorities make it difficult for law enforcement officers to trace criminals engaging in Financial Fraud (Interpol, 2017).

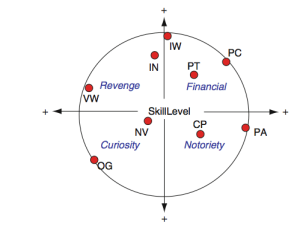

Financial Intelligence can curb Cybercrime by understanding what motivates Cybercriminals. This paper seeks to understand Cybercrime in the context of three types of Cybercriminals – Petty Thieves (PT), Professional Criminals (PC) and Information Warriors (IW). Rogers (2011) originally proposed a nine model classification of Cybercriminals based on what motivates them. Of these nine types of Cybercriminals, PT, PC and IW’s motivations revolve around Money Laundering and Financial Fraud.

MOTIVATIONS FOR FINANCIAL FRAUD

Petty Thieves (PT) engage in Cybercriminal activities to further their criminal activities (Rogers , 2005). They are less interested in notoriety. Their attraction to the Internet and technology is to follow their traditional targets, which include banks and naïve people. PTs learn and acquire the prerequisite skills that can enable them to perpetrate Cybercrime. This group often possesses a maturation of skills and are largely motivated by greed, revenge and financial gain (Parker, 1998).

Unlike Petty Thieves, Professional Criminals (PC) have larger ambitions and a higher set of technical abilities and skills. Like professional criminals within the traditional criminal domain, PCs are motivated to engage in criminal activities by financial and monetary gains. They seek to gain fame and bragging rights; PCs take pride in accomplishing their criminal tasks. However, due to their sophistication, they are rarely caught or attract the authority’s attention. Individuals belonging to this group are mature developmentally, psychologically and chronologically with a high level of technical acumen. They often work with organized Cybercriminal groups who are adept at using Internet technology in furthering their criminal goals (Rogers & Ogloff, 2004).

The Information Warriors (IW) consists of persons who defend and conduct attacks, which are aimed at destabilizing, affecting or disrupting the integrity of information and data systems that control and command decisions (Sewell, 2004; Rogers, 2005). This group is composed of non-traditional as well as traditional state sponsored technology-based warfare outfits. Individuals belonging to this group are highly skilled, highly trained and motivated by patriotism to engage in Cybercrime.

PC and IW are considered the most dangerous Cybercriminals. They are ex-intelligence operatives and professional criminals and are guns for hire (Post, Shaw, & Ruby, 1998; Post, 1998). These individuals being extremely well trained, specialize in corporate espionage and have the access to necessary state of the art equipment for executing their plans (Denning, 1998).

FINANCIAL INTELLIGENCE TO CURB FINANCIAL FRAUD

It is recognized that Cybercrime can be managed through financial Crime Risk Assessment, which is part of Financial Intelligence. There are three prevailing narratives that support this argument. The first narrative is that information technology is creating new services and products, driving disruptive innovation and destroying and impacting the already established business models. Examples include mainframes giving rise to Internet enabled online banking, ATM and the Web driving the creation of person-to-person payments and banking apps. The second narrative is that organized Cybercrime is moving in tandem with innovations to identify and exploit the vulnerabilities and weaknesses of fraudulent gains. According to Ganaspersad and Shirilele (2015) organized Cybercriminals are using fraudulent topologies that mirror the development of products. These topologies include stolen cheques and cards, increased levels of sophisticated Cyber-attacks, attacks on Internet protocols weaknesses and advanced persistence threats. The common thread linked to these narratives includes the increased speed of change in areas of retail payment and banking, and the ability of Cybercriminals to respond with speed (SIPA, 2011).

The third and swiftly emerging narrative emphasizes the convergence of IT security and fraud risk management to overcome the shortcomings of the traditional model which is characterized by constrained communication, shared understanding and separated functions. This narrative emphasizes the need for change, indicating that the existing risk management framework does not effectively guard institutions from financial loss and attack with resultant damage to the regulatory relationships and reputation. It emphasizes the importance of designing agility into the risk management processes for financial institutions to help facilitate proactive response to criminal and innovation threat (Daws, 2015).

Indeed, in line with these narratives, it is widely recognized that Cybercriminals require financing in order to fund their operations. They require sustainable cash flows to fund their operations. Financial Intelligence emerges from this context. It encompasses methods and means used by actors within the financial industry to reveal, deter and disrupt financing of Cybercriminals. Cybercriminals often engage in a range of financial activities with a view to ensuring that the security agents do not disrupt cash flows. Their modes of operations are diverse. They receive donations from unwitting and complicit sources. Common means of their financing include fraud, counterfeiting, kidnapping and extortion. Some actors engage in security schemes and market-based commodities. All these activities are underpinned by a practice referred to as Money Laundering (American Security Project, 2011).

Money Laundering is a process involving concealing illicitly gained funds and making them appear as funds that was sourced legitimately. These are the funds that international financial institutions and security experts seek to curtail by using Anti-Money Laundering practices and policy. Transactions of any nature or amount made via conventional channels are detected and traceable (American Security Project, 2011). Money Laundering allows Cybercriminals to clean up criminal proceeds and disguise their unlawful and illicit origins (Crown Prosecution, 2002). This is often achieved when Cybercriminals hack the government or an organization’s IT infrastructure by means of various malware. This allows them to track people’s online activities and transactions, obtain passwords and other personal information. This way, they siphon billions of dollars worth of intellectual property, technology and trade secrets from the computer systems of corporations, research institutions and government agencies (Nakashima, 2011).

The use of conventional means combined with extensive cooperation between financial industry, governments and international financial institutions can yield considerable success in deterring Cybercrime by combating Money Laundering. However, it is challenging for financial institutions and governments to detect and disrupt Informal Value Transfer Systems like “hawala”. These systems may not comply with the requirements of formal financial systems, which require firms to track and report Money Laundering activities. These systems are by nature abstract and unregulated. This way, they facilitate secrecy and allow Cybercriminals and other illegitimate actors to exploit Cyberspace with increasing regularity and conduct their financial operations without being detected (Passas, 2003). Restricting the organizations’ ability to access resources is an important component of the broader security strategy.

Financial Intelligence is by nature adaptive and requires a broad range of forensics, network analysis, technology complement by effective and smart policies (Bank of England, 2016). By understanding factors influencing current practices and trends in the area of Financial Intelligence, industry leaders and policymakers will be well-informed and empowered to come up with effective judicious policies and private-public partnerships needed to help secure the global financial system, effectively combat threat finance, and facilitate information-sharing.

SIPA (2011) proposes two trends that can enable firms to overcome Cyber threats: collective intelligence and providing technical and professional services. With regard to collective Financial Intelligence, SIPA (2011) suggests that the evolving and distributed nature of Cyber threats requires financial institutions to create a networked and collaborated defence. Within the Cyber security context, collective intelligence involves sharing information concerning remedies, vulnerabilities and threats between security vendors, the government and enterprises. It can inform Cyber forensics to audit areas of suspected and known weaknesses. It can also reveal areas and trends that warranty investing additional security measures. Vendors are developing shared Financial Intelligence features including anonymously injecting data feeds and aggregated data about email addresses, file names, IP addresses, search strings and query into their security monitoring dashboards with a view to help improve security for their users. As suggested by Ganaspersad and Shirilele (2015), the key aim of Cyber security should be to promote the sharing of vulnerability and Cyber threat information between private sectors and the public.

With regard to technology and Financial Intelligent professional services, it is indicated that it is increasingly becoming difficult for traditional Cyber security products namely antivirus scanners and firewalls to thwart every threat created as a result of security vulnerability brought about by mobile, cloud and social computing. Network security analysers and other tools make it difficult for enterprises to use effectively without specialized Cyber security talent and help from other firms. Professional services companies have introduced security offering that integrate human intelligence and analytical and automation capability of information technology platforms to help users cope. These technology offering enable firms to collect, analyse and monitor large data sets in order to identify patterns that suggest any breaches attempted by Cybercriminals. This allows enterprises to respond with more agility to threats. It also allows firms to thoroughly audit Cyber security risks whenever they are expected to disclose their security incidents and risks. Firms are no longer relying on using passive defences to protect against Cyber attacks. As such, joining analytics and automation to human judgment and tapping into collective Financial Intelligence can enable them to lower costs of mitigating Cyber attacks and reduce risk of such attacks (Bissell, Mahidhar, & Schatsky, 2013).

According to Seddon (2015) Financial Crime Risk Assessment should encompass the following: access rights and controls; data loss prevention; vendor management; training; and incident response plan. Adequate access rights and controls such as implementing multifactor authentication are required to help prevent unauthorized access to Information Systems. This includes reviewing controls associated with customer logins; remote access; tired access; network segmentation and passwords. Data loss prevention involves implementing adequate and effective controls in areas of system configuration and patch management, including monitoring network traffic and the potential transfer of unauthorized data via uploads and email attachments (Ganaspersad & Shirilele, 2015).

Vendor Management encompasses controls and practices aimed at selection and evaluation of external providers. These controls and practices include due diligence in relation to vendor monitoring, selection, and oversight. It also includes how to consider vendor relationships are part of the ongoing risk assessment process of the firm (Seddon, 2015).

There is need for adequate training of vendors and employees with respect to Confidentiality of Customer Information, Customer Security and records. According to Seddon (2015) the training should be tailored to encourage responsible Vendor and Employee Behaviour, and on how to integrate incident response procedures into regular training programs. Incidence response plans includes the assessment of System Vulnerabilities, Assigning Roles, and determining which firm, assets, services, or data warrant protection.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, Financial Intelligence is a critical area for unravelling financial networks that support these illicit and dangerous Cybercriminal. The efforts to combat Cybercrime must therefore involve a multidisciplinary approach to help understand enabling factors and driving forces of Cybercrime. The cost-benefit and efficacy of existing Anti-Money Laundering practices should also be taken into account.

REFERENCES

1.American Security Project. (2011). Threat Finance and Financial Intelligence. Retrieved 2017 from https://www.americansecurityproject.org/asymmetric-operations/threat-finance-and-financial-intelligence/

2.Assocham. (2015, June). Current fraud trends in the financial sector. Retrieved 2017 from PWC: https://www.pwc.in/assets/pdfs/publications/2015/current-fraud-trends-in-the-financial-sector.pdf

3.Bank of England. (2016). CBEST Intelligence-Led Testing: Understanding Cyber Threat Intelligence Operations. Retrieved 2017 from http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/financialstability/fsc/Documents/cbestthreatintelligenceframework.pdf

4.Bissell, K., Mahidhar, V., & Schatsky, D. (2013, August 13). Fighting Cybercrime with Collective Intelligence and Technology. Retrieved 2017 from The Wall Steet Journal: http://deloitte.wsj.com/riskandcompliance/2013/08/13/fighting-cyber-crime-with-collective-intelligence-and-technology/

5.Boorman, J., & Ingves, S. (2001, Febuary 12). Financial System Abuse, Financial Crime and Money Laundering— Background Paper. Retrieved 2017 from IMF: https://www.imf.org/external/np/ml/2001/eng/021201.pdf

6.Crown Prosecution. (2002). Proceeds Of Crime Act 2002 Part 7 – Money Laundering Offences. Retrieved 2017 from http://www.cps.gov.uk/legal/p_to_r/proceeds_of_crime_money_laundering/

7.Daws, M. (2015, September 18). Fraud risk management and IT security should converge to protect against organized and cyber crime . Retrieved 2017 from http://financeandriskblog.accenture.com/cyber-risk/finance-and-risk/fraud-risk-management-and-it-security-should-converge-to-protect-against-organized-and-cyber-crime

8.Denning, D. (1998). Information Warfare and Security. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

9.Ganaspersad, R., & Shirilele, N. (2015, July 23). Financial Crime Risk Management (FCRM) Policy. Retrieved 2017 from https://www.hollard.co.za/binaries/content/assets/hollardcoza/pages/about-us/legal-requirements/south-africa/annexure-a–hollard-fcrm-policy_2015-final-approved-by-board.pdf

10.Interpol. (2017). Financial crime. Retrieved 2017 from https://www.interpol.int/Crime-areas/Financial-crime/Financial-crime

11.Nakashima, E. (2011, November 6). Warning as US companies lose out through cyber-spies. Retrieved 2017 from https://www.pressreader.com/south-africa/the-sunday-independent/20111106/282475705615821

12.Parker, D. (1998). Fighting computer crime: A new framework for protecting information. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

13.Passas, N. (2003). Hawala and Other Informal Value Transfer Systems: How to Regulate Them? Risk Management , 5 (2), 49–59.

14.Post, J. (1998). The dangerous information system insider: psychological perspectives. From http://www.infowar.com

15.Post, J., Shaw, E., & Ruby, K. (1998). Information terrorism and the dangerous insider. InfowarCon’98. Washington, DC.

16.Rogers, M. K. (2011). Chapter 14 The Psyche of Cybercriminals: A Psycho-Social Perspective. In S. Ghosh, & E. Turrini, Cybercrimes: A Multidisciplinary Analysis. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

17.Rogers, M. (2005). The development of a meaningful hacker taxonomy: a two dimensional approach. NIJ National Conference 2005. Purdue University.

18.Rogers, M., & Ogloff, J. (2004, Spring). A comparative analysis of Canadian computer and general criminals. Canadian Journal of Police & Security Services , 366-376.

19.Seddon, J. (2015, October 7). Cyber crime – a growing threat to financial institutions. Retrieved 2017 from Cyber crime – a growing threat to financial institutions

20.Sewell, W. (2004). Protecting against Cyber terrorism. Public Works , 135 (3), 39-43.

21.SIPA. (2011, February). Financial Intelligence Department. (2011). Guidelines For Risk Assessment And Implementation Of The Law On Prevention Of Money Laundering And Financing Of Terrorist Activities For Obligors. Retrieved 2017 from Financial Intelligence Department, Bosna i Hercegovina Ministarstvo sigurnosti: http://www.sipa.gov.ba/assets/files/secondary-legislation/smjernicefoo-en.pdf